'Smallwood, Lennon, the gods and me'

The following article by Susan Bourette was published in the Report on Business Magazine in December 2004.

•••

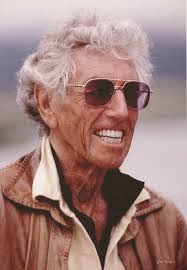

Geoff Stirling pioneered TV in Newfoundland and FM rock across Canada. The next goal for the last media maverick Reincarnation.

The lights are up, the cameras are in place and a

microphone is clipped to the sweater of the man who is at once mogul,

mystic and prankster.

Geoff Stirling is ready for his close-up. It's

the latest take in The Geoff Stirling Story, starring Geoffrey William

Stirling, produced, directed, written and lived by the selfsame Geoff Stirling.

The show has been in production for almost a half

century, ever since Stirling erected Newfoundland's first television broadcast

tower and began transmitting shows like Hopalong Cassidy.

Here in St. John's, they joke that Geoff Stirling

is 4 million years old and 17 feet high.

But in person, he's utterly human.

Standing 6 feet tall, he's thin, "all skin and grief," as the locals

say, and all the more so dressed in black save for the red bandana around his

neck and a silver crop of bedhead that lends him the worn chic of an aging rock

star.

At 83, Stirling knows the production can't go on

forever.

There's only a decade or two left to tie up loose ends.

The rushes have been seen only by friends and family — and by late-night viewers of Stirling's NTV, the dominant station in Newfoundland and an increasingly popular diversion elsewhere via satellite.

In the episode filming tonight, the unwitting guest star is a writer from this magazine.

The rushes have been seen only by friends and family — and by late-night viewers of Stirling's NTV, the dominant station in Newfoundland and an increasingly popular diversion elsewhere via satellite.

In the episode filming tonight, the unwitting guest star is a writer from this magazine.

"Sit down right there, honey," Stirling

commands in a lilting voice, pointing to the chair next to his at NTV

headquarters, a low-slung building on the edge of the Atlantic, a 10-minute

drive from St. John's.

"I hope you don't mind the camera," he says. Before I've had a chance to answer, he's bellowing to the technician, "Mike, have you got her in the centre of the frame?"

I see my head bobbing in a monitor. I can't help noticing it's not a flattering look — slack-jawed, eyebrows hoisted in italicized disbelief.

"Okay, we're ready to roll," he thunders.

Never an enthusiastic performer, I meekly ask, "Mr. Stirling, what are you planning to do with this?"

He leans in close with a wild-eyed stare and points to my tape recorder. "What are you planning to do with this?" hem asks with mock incredulity. Then he stretches his mouth into a wide, sly

grin.

It's just another day at the NTV funhouse, a station unlike any other in the country, or perhaps the world. The corner office likewise is occupied by a media mogul unlike any other, one who diverts a conversation about corporate strategy into reflections on crop circles and reincarnation.

At one point, Stirling declares, "I am whole. I am perfect. I am unlimited."

But the singularity goes beyond the man's passions and persona: Stirling is the last of a breed, the independent broadcasters who pioneered privately owned television in Canada.

In a business now subsumed into a handful of media conglomerates, Stirling is a lonely lion in winter.

For decades, Geoff Stirling ruled as if the island were his personal media fiefdom. He didn't enjoy a monopoly, to be sure, but Stirling was the dominant player, with major outlets in print, radio and television.

Today, he serves as chairman of privately held Stirling Communications International — an enterprise he oversees from his ranch in Arizona when he's not in St. John's.

His holdings include a printing business (Stirling Press) and three province-spanning platforms: NTV, rock radio station OZ-FM and The Newfoundland Herald, a once-scrappy tabloid that is now largely a television and entertainment guide.

His television station is the only one in Canada with deals to broadcast both CanWest Global and CTV programming, much of the former imported from the U.S.

Indeed, although Stirling fulminates about protecting Newfoundland's cultural sovereignty, he's made his fortune by broadcasting American shows such as Survivor, The Apprentice and The Young and the Restless.

Still, there's no denying him his reputation as a trailblazer.

His TV station was the first to broadcast 24

hours a day in North America, and he is credited with revolutionizing the FM

radio dial in the late '60s.

A 1974 documentary in which he co-stars, Waiting for Fidel, is a cult classic, credited as the first "stalkumentary," an influence on the likes of Michael Moore.

A 1974 documentary in which he co-stars, Waiting for Fidel, is a cult classic, credited as the first "stalkumentary," an influence on the likes of Michael Moore.

"Geoff Stirling's been a visionary,"

says Rex Murphy, the CBC broadcaster and fellow Newfoundland native. "In

many ways, he was a somewhat awkward anticipation of Moses Znaimer."

A visionary is bound to run into static and interference, and these days the noise is coming from all sides for Stirling. He's in the fight of his life with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which is demanding NTV produce more Canadian content than ever before.

A visionary is bound to run into static and interference, and these days the noise is coming from all sides for Stirling. He's in the fight of his life with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which is demanding NTV produce more Canadian content than ever before.

OZ-FM, meanwhile faces fiercer competition for rock listeners. And The Newfoundland Herald is losing eyeballs to on-screen TV-listings services: Its circulation has tumbled by more than 50% since 1997, to 20,000 across the province.

He's also confronting bigger powers in TV who

would love nothing better than to fold Stirling's profitable venture into

their own empires.

He'll wage those quixotic battles in due time. Meanwhile, there are hours of programming to fill. That's why, in the early morning hours a week after our meeting, my phone rings. It's Stirling, informing me that my interview with him — largely unedited and including more than a few cuss words and testy exchanges — will be beamed across the province at 3 a.m. Talk about reality TV. I didn't even sign a waiver.

The Geoff Stirling Story has played out in

episodes like the one I

wandered into — vignettes captured almost

surreptitiously, aired late in the Newfoundland night and then immediately

archived for "the time capsule" (Stirling's term). The story

stretches back to the time before television.

Reel 1. Establishing shot: Wide angle of Stirling in his early 20s, lying on an embankment beside a swamp in the Honduran jungle.

Reel 1. Establishing shot: Wide angle of Stirling in his early 20s, lying on an embankment beside a swamp in the Honduran jungle.

It's 1946. He's dressed in hip waders and has a rifle at the ready.

He's a long way from home, fresh out of

university, doing an improbable thing for the sports-star son of a St. John's

restaurant owner.

But it was here, in Honduras, that he had the vision. It came down from the sky while he was hunting alligators — stacks of tightly bound newspapers.

Stirling wondered: If The Miami Herald can get all the way to readers in the Central American jungle, why can't I get a newspaper to the outports of Newfoundland?

Stirling didn't much like shooting gators for the shoe-and-handbag trade anyway. He headed home with a scheme to launch his own tabloid.

He'd already developed a taste for journalism,

having worked as a stringer for Time and the Chicago Tribune while studying

pre-law at the University of Tampa.

Back home, his plan met with a collective sneer. Among the most vocal skeptics was the journalist and politician Joey Smallwood.

How could Stirling succeed, Smallwood pressed him, when his own paper had folded? Stirling told him: "Joe, you've got nothing but politics. I'm going to have ghost stories and comics and all kinds of stuff."

With a start-up fund of $1,000 that he'd saved from working at his father's restaurant, Stirling purchased 60 tonnes of newsprint from Smallwood's defunct paper and launched The St. John's Sunday Herald, a striking alternative to the St. John's dailies, the Evening Telegram and the Daily News.

For the first four years, he wrote practically everything in the 100-page weekly save the letters to the editor.

To build readership, he had the Herald air-dropped onto the ice floes where sealers toiled for long stretches during the winter hunt.

"I think the Herald's beginning says something about the cornerstone of Geoff's thinking," says his son, Scott, who, although he took over the operational reins at the company 15 years ago, still relies on his father as counsellor and corporate persona.

"He's always been a free spirit and a freethinker. Somebody once said that while people typically have two or three voices going on in their head, Geoff must have eight or nine. He just sees things that other people can't. He's not afraid to try something everyone else believes will fail."

The Herald hadn't been around long when Stirling waded into a debate over nothing less than the Herald joined forces with some of the island's most prominent businessmen — led by Ches Crosbie, father of future federal minister John Crosbie — in an anti-Confederation crusade.

To the anti-confederates, the best option for Newfoundland, which had been reduced to a virtual ward of the Crown by years of hardship, was economic union with the United States.

Stirling threw himself into the cause: When he wasn't lobbying senators in Washington, he was proselytizing in the Herald.

It was a battle his side nearly won. Newfoundland became the 10th Canadian province in 1949, but with just 52% of voters having opted to join Confederation.

Reel 2. Establishing shot: Medium shot of Premier Joey Smallwood sunk in a red leather chair. Seated beside him are his friends Don Jamieson and Geoff Stirling. They raise a glass in a toast to a new beginning.

It's the early '50s. Stirling has licked his wounds and put behind him the bitterness over his beloved Newfoundland's fall into the embrace of the Canadian federation.

Although he'd worked to defeat Joey Smallwood and his plan, the two men bonded thanks to their shared love of their newly minted province.

It was a time when politicians and journalists freely associated with each other and made common cause when their interests coincided.

Along with Jamieson, another vehement anti-confederate who would serve as political minister for Newfoundland in Pierre Trudeau's cabinet in the '70s, Smallwood and Stirling formed a powerful triumvirate in Newfoundland's new era.

In a place that had long been ruled by a few merchant-class family dynasties, the three men were eager to exploit the power shift that came with Confederation.

Stirling and Jamieson, the latter well-known in the province as a radio announcer, dreamed of a broadcasting empire.

They planned to bring their own radio station to the province (which had only the CBC and some small religious outlets on the air), to be followed by a television station a few years later.

Smallwood smoothed the way with federal regulators so that Jamieson and Stirling were granted their licences for TV and radio, both with the call letters CJON.

Stirling then went to CBS-TV in New York, cramming an in-house, two-year television course into six weeks.

By the summer of 1955, his station was on the air; Jamieson was featured as news anchor, seeding his political popularity.

Nationally, CJON joined the loose band of independents that would eventually form the CTV network.

Stirling's monopoly lasted until 1962, when the CBC was granted a TV licence.

He spent two decades building his empire, picking up radio stations (or sometimes contracts to run them) across Ontario and Quebec.

In the mid-'70s, his TV station took the novel step of broadcasting around the clock.

Night-owl viewers didn't know what to expect — they might catch licensing hearings or the company Christmas party, or one of the heated dialogues between Stirling and Smallwood, often on the same themes as their National Film Board documentary, Waiting for Fidel.

(The two never do get to interview Fidel Castro; while they're waiting, they talk.) In these wee-hours exchanges, Stirling, the free-enterpriser, took the right-wing position; Smallwood, the onetime socialist, the left.

Spurred on by a few bottles of Blue Nun, they would often debate till dawn.

Stirling's outlets championed whatever cause

inspired their proprietor.

Still sniggering over Stirling's claims to have

been cured of rheumatoid arthritis by liquid gold injections, few

Newfoundlanders paid attention in the early '70s when he got on his hobbyhorse

about gold again, urging them to buy the stuff, as he'd been doing.

Stirling says he'd got an insight from talking to a man in Tahiti: Prices had to go up. True. The price of an ounce of gold sank as low as $35 (U.S) in 1970; by 1980 it had soared as high as $892 (U.S). Stirling made a killing.

Stirling says he'd got an insight from talking to a man in Tahiti: Prices had to go up. True. The price of an ounce of gold sank as low as $35 (U.S) in 1970; by 1980 it had soared as high as $892 (U.S). Stirling made a killing.

Memorial University business professor Dan Mosher

says Stirling's attempt to share the wealth says something about the man.

"Any other individual might simply worry about amassing more for himself.

But [Stirling has] always tried to help improve things in his own way for the

people here."

Reel 3. Establishing shot: A studio booth in London.

Reel 3. Establishing shot: A studio booth in London.

Inside, there are four people: Scott Stirling,

his father, Geoff, Yoko Ono and John Lennon.

It's 1969, shortly after the Beatles have released Come Together, a Lennon number that began life as the campaign song for acid-guru Timothy Leary's intended run against Ronald Reagan for governor of California.

The song, cryptic though it was, mesmerized Geoff and Scott, a Lennon fan. From the Londonderry Hotel, where the two were staying on vacation, Stirling telexed a note to Lennon. It said, "I've heard your Come

Together. So here I am. Geoff Stirling."

A few hours later, they were seated in Apple Studios, recording the first in a string of interviews with Lennon that Stirling would later broadcast on his Canadian radio stations.

"I look back on that first interview and I realize how profound it was," Scott says. "It was a philosophical discussion about the forces of good and evil, and how Lennon was trying to use his music to socially improve civilization."

Stirling used it to revolutionize FM radio in Canada. By the late 1960s, FM radio was a profitable niche offering easy-listening and light classical music.

Stirling was determined to turn his stable of stations into a different form, one already reverberating south of the border — "tribal radio."

His Montreal radio station, CHOM-FM, was the first such experiment in Canada. It was the quintessential hippie FM rock station, a smoky crash pad where listeners could tune in for an hour and never hear what time it was, let alone a word about sports or the weather.

One of Stirling's new crew took to the airwaves and cast the I Ching for four hours to figure out if the format change would work. There were endless spins of the Beatles' Abbey Road, interspersed with meditation chants and discussions on cosmic consciousness.

Jim Sward, who later became president of Global Television, was 24 when Stirling hired him to run his mainland radio operations from Montreal.

"We were a mix of those on a social mission and button-down, professional broadcasting types like myself," Sward recalls. "Somehow the professionals co-existed somewhat harmoniously with this group of goddamned hippies.

"Geoff was so courageous. He did do things that offended and disgusted me. He can do things that are hurtful. But I've never met another person with that kind of charisma. I have great affection for him and if I saw him now, I'd give him a big hug."

Listeners in Montreal were impressed too. The station's novel sound gave CHOM a lock on the teen and young-adult market. Stirling introduced the rock format to the rest of his radio empire, which swelled to 13 stations, including CKPM in Ottawa and CJOM in Windsor.

Reel 4. Establishing shot: High atop a mountain in the Himalayas in the '70s. Holding beads and wearing long flowing robes, Geoff and Scott Stirling are seated in the lotus position next to a swami, in deep meditation.

Cue sitars.

Just as his stations devotedly played Lennon's work, so did Stirling follow the Beatles up the mountain, embracing Eastern mysticism, meditation and the same group of holy men.

The search for meaning was inspired by the spectre of death. Scott was 20 when his doctor found a large lump in his neck and diagnosed Hodgkin's Disease, a cancer of the lymphatic system.

A second doctor told him not to worry: It was a cyst. Scott headed for India, wanting to believe his second doctor and hoping that medical treatment could wait.

Geoff followed him a month later.

"Geoff told me that he was going to devote all his energy to finding a cure for his son," recalls Sward, Stirling's radio boss. "He left and I didn't see him for nearly a year."

During the trip, war broke out between India and Pakistan, and the Stirlings found themselves stranded for months. As bombs dropped around them — and with Scott's health at the forefront of their minds — they began to seek out India's holy men for answers.

"We went through that together and I think it changed me and it changed Geoff. That's why India was so significant to both of us," Scott says. Father and son both became ardent proponents of yoga and meditation.

Scott believes it was his conversion to vegetarianism that prevented the lump on his neck — which was in fact a cancerous tumour — from growing. His cancer went into remission.

After the India trip, Stirling was wont to spontaneously show up at CHOM with his swami and put him on the air. But Eastern religion was no mere dalliance for the Stirlings.

Clicking through the corners of the NTV website (ntv.ca) can resemble a lecture in world religions, with links to New-Age websites and Stirling's self-published book, In Search of a New Age.

The NTV site also features a Stirling father-and-son creation, a comic-book spiritual superhero called Captain Newfoundland, who fights evil with telepathic powers and a keen understanding of the collective consciousness.

The backstory is that Captain Newfoundland is descended from divine creatures that once inhabited the lost continent of Atlantis, now the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Scott believes that daily meditation is crucial to steering the family empire. "This job demands a lot of concentration and a lot of focus. I think the business has benefited from my meditation.

I don't think that either Geoff or I could live

without it."

The two had to rely heavily on their practice in 1977 when tragedy struck. Scott's 19-year-old sister, Kim, was killed in a car accident.

The two had to rely heavily on their practice in 1977 when tragedy struck. Scott's 19-year-old sister, Kim, was killed in a car accident.

It was a life-changing event for the elder

Stirling.

"When that happened, I think Geoff reassessed where he was," Scott says. "He thought: What's this all about? Do I want to just keep expanding? Or is there something more to life than this?"

Stirling consulted his family, asking them what assets they wanted him to keep. But his family left the decision to him. Stirling sold off all of his radio stations on the mainland and retreated to Newfoundland.

Reel 5. Establishing shot: Close-up of Geoff

Stirling in the St. John's studio.

The clicking sound of a camera shutter fills the otherwise silent room. Stirling's smiling, but he's not happy.

The clicking sound of a camera shutter fills the otherwise silent room. Stirling's smiling, but he's not happy.

The photographer is politely asking Stirling to

work with him, but he proves to be a reluctant subject.

If these were promotional stills for a Stirling production, he'd be more co-operative.

But, no, it's a shoot for the magazine that you're reading. It's one thing to star in your own biopic, it's another completely to yield creative control.

If these were promotional stills for a Stirling production, he'd be more co-operative.

But, no, it's a shoot for the magazine that you're reading. It's one thing to star in your own biopic, it's another completely to yield creative control.

The photograph really isn't what's bothering Stirling though.

It's something the lens can't capture, something

happening behind the scenes. The office is a flurry of paper and faxes. Today

is the deadline for the next round of documents to be filed with the CRTC

explaining why NTV can't possibly meet the regulator's demands

for increased Canadian content.

The CRTC is fiddling with NTV's broadcast day, effectively shortening the time period in which the station has to air its allotment of Canadian content.

The way NTV sees it, it's vicious and punitive.

Under the regulator's new rules, the broadcast day goes from 7 a.m. to 1 a.m., instead of the formula of 6 a.m. to 1:30 a.m. that's been in place since the 1970s — a concession from the CRTC that allowed NTV to take advantage of simulcast opportunities despite its unique time zone.

The upshot is that the station can no longer count its early-morning newscast toward its Cancon quota. NTV will have to generate more programming, and that won't be cheap.

And it could put a serious dent in the new hybrid model that NTV has become.

Today, not just Newfoundlanders, but some 1.3 million people between Vancouver and St. John's — and as far south as the Caribbean — watch NTV each week.

Adding satellite transmission to conventional signals, NTV started broadcasting continentally in 1994. In 2002, its growing non-Newfoundland audience led to a parting of ways with CTV, of which it had been an affiliate.

Paul Sparkes, a spokesman for CTV parent Bell Globemedia Inc., says that while NTV wanted to keep airing the network's top programs, it didn't want to show the corresponding national commercials.

So NTV was competing with CTV for both viewers

and advertising.

"One reason our relationship with NTV is different is because one-third of its audience is now outside of Newfoundland," Sparkes says. "They are competition in a way that they weren't before they went to satellite."

Still, CTV continues to allow NTV to air news shows such as the evening national news and Canada AM, in exchange for NTV news reporting.

So the network that NTV most resembles now is Global — a lot of shiny American imports and a few perfunctory domestic productions, done on the cheap.

The local content consists of news programming and live-entertainment shows like the surprisingly addictive Karaoke Idol (which is just what it sounds like, filmed in a bar) and George Street TV (sketch comedy featuring two comedians, a couch on the sidewalk and whoever happens by).

Stirling could, of course, pledge to do more and better original programming. But the best-behaviour face that private-sector broadcasters put on to satisfy the CRTC has a nervous tic in Stirling's case — his tendency to mouth off.

It's true too that Stirling's causes these days don't have the historic sweep of the battle over Confederation.

He has used his media machine to promote various New Age ideas and to lobby the producers of Survivor to locate the next edition of their show on Kellys Island, an uninhabited scrap of rock near St. John's.

But he does still take on matters of public policy, calling for the renegotiation of Newfoundland's Churchill Falls energy agreement with Quebec and decrying another Labrador deal — the one the province struck with Inco for the Voisey's Bay nickel development.

In 2002, Stirling suggested that members of the provincial legislature who voted for the Voisey's Bay deal should face criminal charges.

"I'm not anti-anything. I'm just pro-Newfoundland," Stirling says of his pronouncements. "Communicating is everything. I am in the unique position to have the opportunity to contribute to the culture that's unfolding here."

But the line between Stirling's role as a media owner and his role as a citizen is too faint, according to Noreen Golfman, a board member of Friends of Canadian Broadcasting and a professor of English and Film Studies at Memorial University in St. John's. "He owns the station and uses it to promote his own ideology," Golfman says.

"He'll get right on television himself to say what Newfoundland should be doing, or what Canada should be doing. Just imagine if [Bell Globemedia president] Ivan Fecan did the same. It would be a huge flap."

In a place that's still rich with shared family history, where the first question is always, "Who do you belong to?" the answer in Geoff Stirling's case isn't so clear.

Who is going to defend his interests now? In another era, a phone call from Premier Joey Smallwood might have fixed everything.

Stirling has indeed enlisted Premier Danny Williams to write the CRTC, but it's not like Stirling's calling up his buddy any more.

In a different time, faced with bureaucratic intransigence, Stirling would have stood aligned beside a powerful group of independent broadcasting affiliates across the country, staring down the CRTC together.

Today, seated against the black backdrop of the cavernous room, peering into the blinding studio lights, Stirling looks vulnerable.

"I'm not ashamed of what I've tried to do.

Maybe I've bitten off more than I can chew," he says, pausing reflectively

for a moment.

"They'd love me to sell," Stirling tells me. He won't say who wants to buy his crown jewel, although there are whispers in the industry that all of the private-sector national broadcasters — CTV, Global, CHUM — have designs on his station. None is expressing interest publicly. All Stirling will say is that he's had four informal offers in recent years.

But with three generations of Stirlings now

working in the family business — grandson Jesse is in charge of marketing —

Stirling says the family is here to stay. Indeed, the eve of the 50th

anniversary of his introduction of television to Newfoundland would hardly be a

suitable time to sell.

"I'm sure that if NTV were sold to a

national company," Stirling says, "we'd lose our sovereignty, which

is the only sovereignty we have right now — television and radio owned by

Newfoundlanders.

"No," he continues, his voice shaking

now, "I'll never sell out. They'll never drive me out. I'm going to keep

doing it my way."

With that, the interview is over. The lights are dimmed. Stirling removes his microphone and heads to the door, bidding me goodbye as he steps into the foggy night.

With that, the interview is over. The lights are dimmed. Stirling removes his microphone and heads to the door, bidding me goodbye as he steps into the foggy night.

Two days later, he calls me. I can hear it in his voice. He's in much better spirits. Even an auteur and resident philosopher-king is entitled to a bad day.

Now, the clouds have lifted, the view from the mountaintop is clear. He'll soon be off to Arizona. Meditating on all of his accomplishments in this lifetime, and what's left to come on life's stage.

"This is my movie. I'm the writer, the

producer, the director and the hero," Stirling tells me. "In my new

movie, my reincarnation, I may not come back to Newfoundland. I may not even

come back to this planet."

Wherever he is, he'll look back on this movie and smile broadly, knowing that it was he who was truly Captain Newfoundland.

Wherever he is, he'll look back on this movie and smile broadly, knowing that it was he who was truly Captain Newfoundland.

Comments